Have we really lost it too?

Have we really lost it too?

This most important holiday, which remained the glue of the nation and unconditionally united everyone. It was the backdrop of life, an element of unquestionable sanctity, a state symbol, the foundation of the legitimacy of the late Soviet power—and at the same time a family story, a private case of common mourning.

Family memory was organically integrated into the state. And if something was missing in the state, the family filled in the gaps, seemingly without contradicting the general discourse. In any case, from childhood, from the seventies, I remember the image of the Eternal Flame on TV and always stood for a minute of silence next to the line of my grandmother's medicines around the portrait of my uncle who died in the war—a 19-year-old Jewish boy. And the minute of silence was not announced by the first person in the state. That incredible degree of privatization of the holiday by one person did not yet exist.

On home bookshelves stood (and still stand) all of Simonov, all possible Ehrenburg, there were military poets, and Okudzhava, and military writers, Astafyev, Bykov, Vasiliev. Something had to be read as part of the school curriculum, but without excessive hysteria and tearful imposition. It was only later that the silences, lies, and sometimes false pathos became clear, which contributed to the strengthening of the already dominant position in the Soviet system of the military-industrial complex and the army, which in many ways undermined this system with their appetites and aggressiveness. And the fear of the truth. And stories with its eradication, as it was with the banned book by Alexander Nekrich, with the 1941 diaries of Konstantin Simonov, and much more.

Who could have thought that all this could not just return, but take place as a cherished failure in historical memory, as a conscious amnesia, turning back into white spots, white patches what had long ceased to be so. Myths return, which are forbidden to refute. Pathos is incensed, which is museified and fixed with cinematic special effects. Victorious triumphalism replaces mourning and repels memory.

For them, at the top, it is easier to do today because even with all the achievements of historical science, with all the numerous publications, in the mass consciousness remain only Putin's pathos and the equating of the SVO to the Great Patriotic War. The transformation of the "special operation" into a direct continuation of the Great Patriotic War, which has now turned into a confrontation not only with Hitlerism but with the entire West, which appeared as an enemy of Russia in different guises—sometimes with the face of Napoleon, sometimes Hitler, sometimes today's leaders, united under the brand "Eurofascism".

Instead of knowledge, understanding, mourning—mythology, slogans, triumphalism. We did not know defeats—only victories. Truth and justice are on our side. The whole country supports the SVO. All these three theses of Putin from the speech on May 9, 2025, contradict historical, moral, sociological truth.

The falsehood, like a radar, was acutely felt by the laureate of the Stalin Prize of the second degree for 1946, a sapper, a native of Kyiv, Viktor Platonovich Nekrasov, author of the story "In the Trenches of Stalingrad." He, like no one else, did much to preserve the memory of the Battle of Stalingrad, as well as other, covered in silences, memory—of Babi Yar. And it was especially painful for him when under the red banner, under the red star, the Soviet Union entered Prague in 1968, and in 1979 got involved in the war in Afghanistan under the guise of the still mysterious "international duty." Nekrasov then called this star the star of shame—already being ostracized, humiliated, and pushed into emigration.

Thus, the attitude towards the red star was divided. And exactly so now is the holiday, which once united us all, and now divides. It is now Putin's, they say about the war itself that it is the historical predecessor of the SVO. Next to Putin now stand not Chirac and Bush, but Chairman Xi and the leaders of African republics. On Red Square, it is not "Normandie-Niemen" that marches, but the army of Myanmar. What relation do all these countries (except for China, which was also considered an ally in that war) and soldiers have to the Victory, the Victory that we were proud of since childhood, feeling like true heirs of the victors?

Historical voids are forming—the transmission of family memory is almost halted. And therefore, this lost-content historical void is easily filled by the state with official propaganda clichés. Paradoxically, the same "Immortal Regiment," intended as a civic movement to support precisely private memory, has turned into yet another Kremlin PR project and is full not so much of mourning as of the same flat triumphalism.

What can today's parents tell small children if they allow pilot caps to be put on infants' heads, and in kindergartens, they play out the receipt of a death notice by a mother. The cult of Victory turns into a cult of war, mourning for the soldier—into a cult of heroic death. What do they know about death notices, what do they know about the feelings of people more than 80 years ago? Who and what can tell them? People of the forties, fifties, sixties, partly seventies of birth still knew something, could pass something on, but many of them are also poisoned by the mythological pathos void of Putin's model of Victory. It means they remembered poorly, absorbed poorly what they could still absorb in childhood and youth. Or they were left with the same Brezhnev pathos, which became the forerunner of Putin's pathos.

"No one can reproach our children for not giving all of themselves to the Motherland,"—wrote to my grandmother her sister in 1943, when her children died from the consequences of the Leningrad blockade, and my uncle died at the Kursk Bulge. Even small children gave themselves to the Motherland—it was at least some psychological compensation for the deaths, an attempt to explain the unbearable. A torrent, a wave of unending grief, breaking through in endless letters that my grandmother wrote to her deceased son, that is, to herself. And her husband at that time was serving a sentence under Article 58 in the Komi ASSR. However, with the right to correspondence, but what did he feel when he learned about the death of his loved ones, about what was better not to know. There, beyond the Arctic Circle, he died in 1946.

There is no fullness of history without the balance of memory of the war and Stalinism, of repressions. A friend of mine wrote on his channel on May 9th that on the holiday he remembered "Ilyich's Gate" by Marlen Khutsiev. Namely, the episode when one of the main characters, Sergey, reflects on the fact that there are things in life that need to be taken seriously. "And what do you personally take seriously?"—"The revolution, the song 'The Internationale,' the year 1937, the war, the potatoes." Potatoes, because they saved the hero of the film with his mother during the war. The characters in the film are in their twenties (the version of "The Gate" is called "I Am Twenty," although during the prolonged, due to censorship, filming the actors themselves managed to grow up), they live already in a peaceful, more free—after Stalinism—time, and therefore it is harder for them to find support. But then it was still possible to find it on the basis of common conventions—romantically presented revolution, wartime childhood, but also knowledge and memory of the year 1937.

Frame from the film "Ilyich's Gate." Director: Marlen Khutsiev

In today's circumstances, there is no such seriousness. There is no continuity of some conventions, except, of course, the Great Patriotic War, which for the current generations is something abstract and now also pathos-filled, and for the generation of Khutsiev's boys was something concrete, something they felt and experienced.

Two or three years later, Khutsiev will show another film—"July Rain," about a generation of those over thirty, who are tired and doubtful, having left the thaw behind and entered real adult life with its compromises. Fatigue and disappointment run through this otherwise Antonioni-toned film. However, it ends with a scene that tries with all its might to preserve the feeling of generational continuity: the faces of twenty-year-olds, born immediately after the war, in a crowd of veterans at the Bolshoi Theater. The relay of generations. But will it happen? It happened, but not in everything. And then it disappeared, quieted down, died, and was replaced by Putin's myth and his "special operation." Isn't it clear that what is happening today does not restore continuity, does not unite generations, but tears this last connection?

The young generation of Khutsiev had at least potatoes. With the war and the year 1937. And with the ideas about the revolution, they were lucky, but then even this romance "in dusty helmets" quickly faded away. This conversation from "The Gate," for which Khrushchev fiercely scolded the film, remained. The dialogue of a 23-year-old son with a 21-year-old father who died in the war: he has nothing to advise his son because he is younger than him. How is this possible, shouted Nikita Sergeyevich, with the presence of the Party Program, the program of building communism.

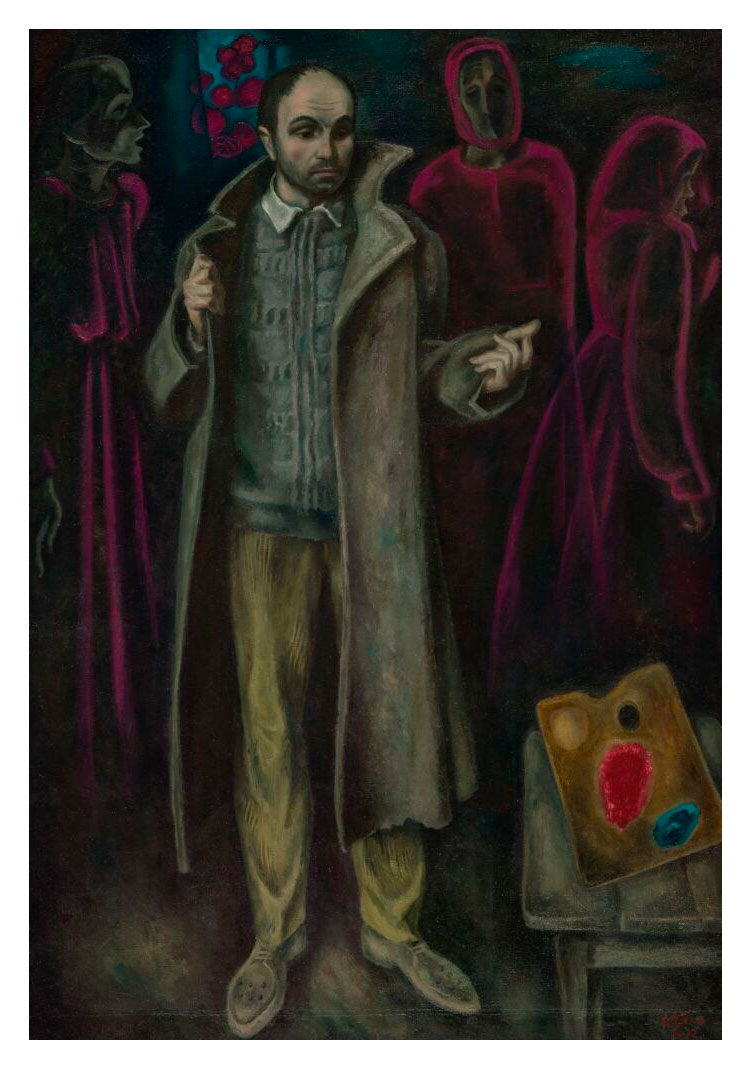

In 1972, artist Viktor Popkov, practically a peer of Khutsiev's characters, by that time losing support and faith, completed his famous painting "Father's Overcoat": a balding man, already entering the period of maturity, the artist himself, tries on his father's overcoat, and it is too big for him. But this is support. Support of memory. Support consisting of those very serious things.

In 1972, artist Viktor Popkov, practically a peer of Khutsiev's characters, by that time losing support and faith, completed his famous painting "Father's Overcoat": a balding man, already entering the period of maturity, the artist himself, tries on his father's overcoat, and it is too big for him. But this is support. Support of memory. Support consisting of those very serious things.

We all came out of this father's overcoat. But its size has increased. And for those who invented the myth of the SVO as a "war-continuation," it does not fit. Too many thoughts, doubts, reflections are hidden inside the overcoat. Too much genuine grief. Grief for peace, so that it does not repeat, and not so that "we could repeat." Meanwhile, now you just need to march and speak in slogans and the language of hate. And hate the whole world.

Has historical memory died? But it is preserved in us. Preserved in friends and relatives. Those for whom May 9th is a family, not a state holiday. They, these two versions of history, have diverged. But May 9th, Victory Day, remains.

One of those things that should be taken seriously.

* Andrey Kolesnikov is considered a "foreign agent" by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.